.avif)

The water environment can profoundly influence the planning of towns and cities. Settlements may vary greatly depending on their location within the river catchment (see Chapter 2 > LifE: Integrating Design with Water) and the type of waterfront, be it coastal, river, lake or canals (see Chapter 1 > Water: Friend or Foe?).

This chapter explores some of the approaches to planning for different waterfronts – not solely based on risk, but also on quality and character. We establish a key regeneration approach to activate the water and enhance the spatial organisation as well as considering several waterfront types at a neighbourhood scale.

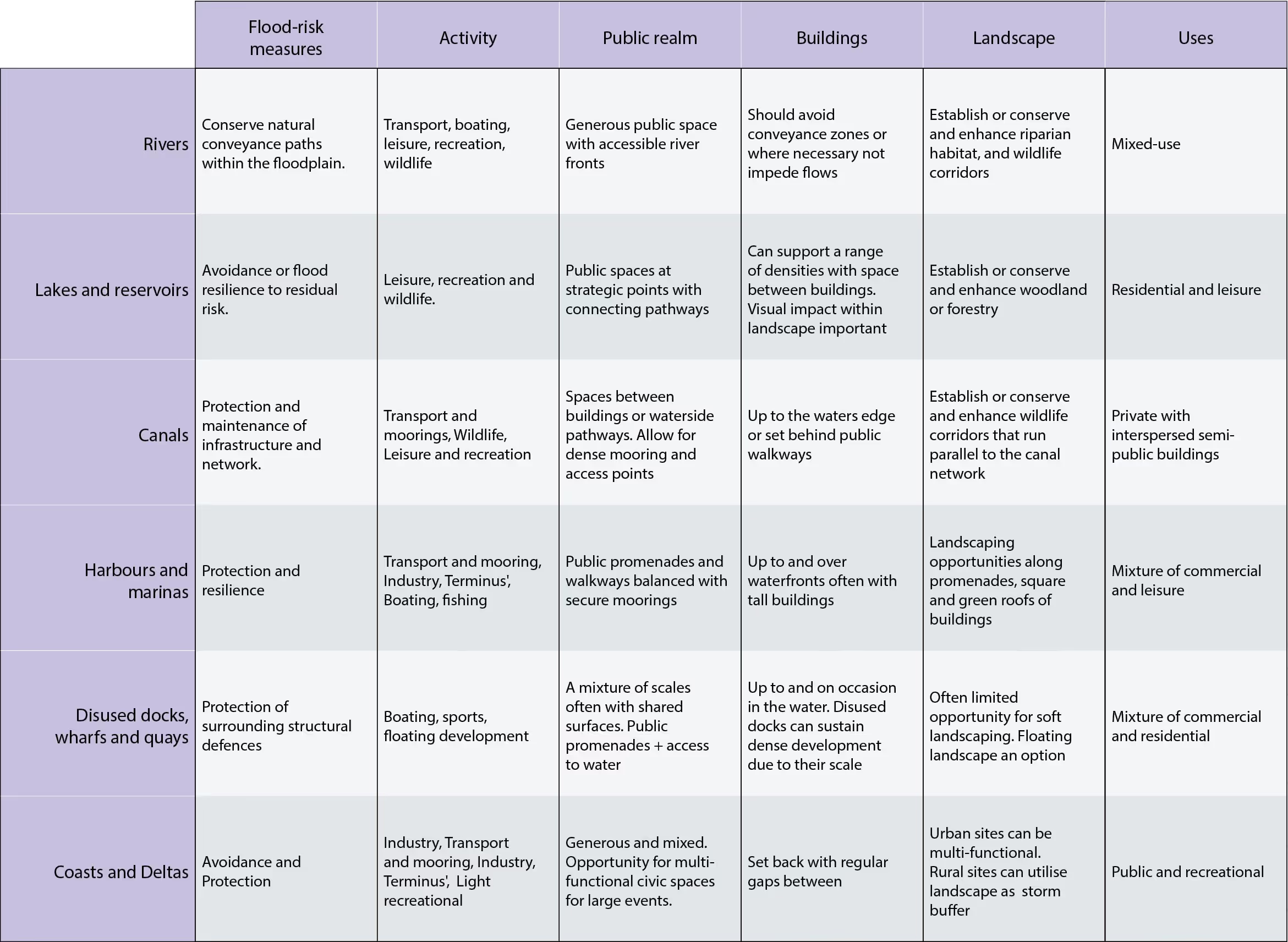

Man has transformed waterfronts from their natural state. Rivers have been controlled, canalised and straightened. Marshes have been drained and built upon. Docks have been excavated, expanded and abandoned. Canals have been dug between rivers, seas and even oceans (see Chapter 1 > Water: Friend or Foe?). In this chapter there are six main types of waterfront explored:

rivers and deltas

lakes and reservoirs

canals

harbours and marinas

docks, wharfs and quays

coasts

Each of these waterfronts has a different character and no two waterfronts are the same. Despite that, many of the problems and issues facing cities around the world are similar and there are some common themes emerging, including urbanisation, pollution, development pressure and flood risk.

The following section explores the changing role of waterfronts and what can be done to make them into successful spaces for the 21st century. The examples are predominantly urban but many of the concepts could be adapted for less urban sites.

Historic waterfronts and waterspaces are frequently found to be at odds with the needs of the 21st century population that now occupy them. The original functions have often migrated to more modern facilities on the outskirts of cities, leaving large areas redundant. Many former working docks, harbours and seafronts have been transformed into marinas and leisure destinations, and surrounded by new residential districts. But many of these have failed to address what to do with the water, bar the inclusion of a marina or a historic boat for good measure. Old industrial structures remain as relics or are converted into museums or condominiums. Yet this approach often lacks the vision and aspiration that established these great edifices in the first place.

Riverfronts, harbours, docks and canals have been radically transformed by industry. The changes, driven by function, were typically pragmatic and sometimes lacking in human scale, but they were also sometimes ingenious and inventive, leaving behind a rich industrial legacy.

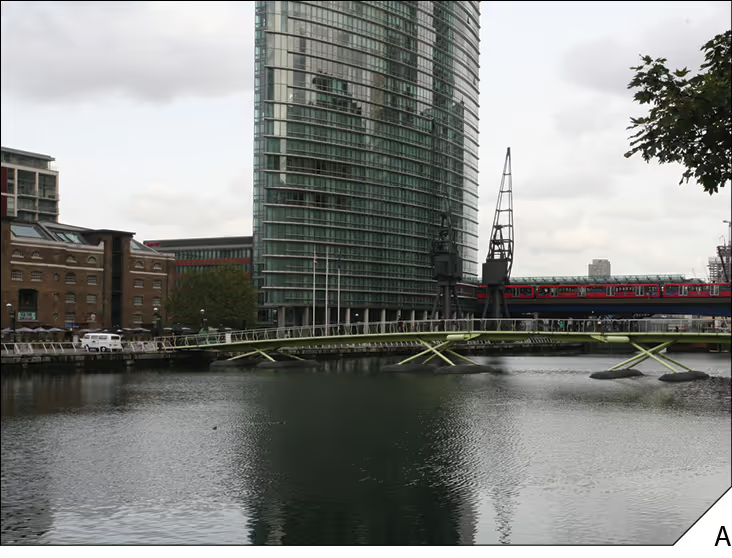

As industry has moved out of cities it has left behind abandoned, often polluted, wastelands and a problem for the next generation – but there have been many examples of bold regeneration. After London’s Docklands ceased operations in the 1960s, many of the old docks were filled in for development. Plans for redevelopment were drawn up almost immediately, but it took a further two decades for Canary Wharf, complete with automated overhead railway, to be realised in the 1980s. Yet within this plan, little attention was given to the use of the waterspace other than as heritage and picturesque backdrop. Figure 4.1 shows the West India Quay with Canary Wharf tower on the right and now occupied by a number of Dutch barges.

In New York, the Chelsea Piers were once used for docking great ocean-going ships such as the Titanic. They were redeveloped for recreation as part of the Hudson River Park. The Chelsea Piers Sports Complex was formed in 1995 on four of the piers over the Hudson River (Figure B).

Almost all city planners place stock in the need for cultural or iconic waterfront buildings, such as the Sydney Opera House, the Venice Campanile, the Oslo Operahuset, the Three Graces in Liverpool and the Bilbao Guggenheim – a building that is frequently cited in regeneration plans thanks to its continued success in bringing Bilbao to international attention since its completion in 1997.

Despite the architectural prowess of many of these buildings they are mostly ‘black boxes’ containing museums, galleries, conference centres or opera houses, none of which rely on or activate the water, and could equally be located elsewhere. They rely on sculptural forms and waterfront settings to create a picture postcard view, but it is the visitors that create the animation and often the buildings have little visual engagement with the water. Many add to the skyline by creating bold silhouettes or to the waterline in beautiful reflections, but their main benefit is as catalysts to regeneration.

In the past, the waterfront was the natural home for amusement parks, such as Luna Park, Coney Island and the Vienna Prater. These included striking landmarks, like Ferris wheels, roller coasters and towers (such as the Brooklyn Parachute Jump), which also offered spectacular views when enjoying the rides. The success of these landmarks is in the public realm, and increasing the footfall and the visual engagement with the water. In Amsterdam the EYE cinema museum, along with a free and regular river ferry bus, is helping to attract visitors from the heart of Amsterdam to the north banks of the IJ, which in turn is benefiting the expansion of the city into this area.

The most successful waterfronts are the ones that provide more than just the landmark building. They create multifunctional neighbourhoods, with the right scale and quantum of public realm, which have a successful mix of uses and that work with the water to locate the most vulnerable of these uses in the lowest flood risk areas. This approach is well illustrated in HafenCity, Hamburg, Germany, which incorporates several landmark buildings in a multifunctional redevelopment, where 37% of the ground area was designated public space. Buildings are protected from flooding by raising the development on plinths on top of basement car parking, while the public realm steps down to engage with the water. “Once its construction is complete, HafenCity is expected to welcome up to 80,000 visitors a day.”

To make a successful waterfront it is important to find the right balance between the character of the public and private spaces, the land use and frontage, the activity on the water, the destination/landmark and the transport/movement. This is explored and illustrated for each type of waterfront below.

Many cities are founded on rivers for the convenience of transport, water and sanitation. In the UK, by the end of the Industrial Revolution rivers in urban areas had become thick with sewage, domestic and industrial waste and were considered biologically dead. Rivers in developing nations are suffering the same fate, where they are frequently used to dispose of solid as well as liquid waste. As rivers grew more polluted higher-value property was located away from waterways. Cities were reorientated around rail and road connections, which provided cheaper and faster means of transport.

In Europe in recent years, many rivers have been cleaned up and EU combined with national legislation has helped to penalise polluting offenders. As the rivers have been cleaned, the value of these waterways for leisure, views and open space has risen. Developers have built many new luxury properties overlooking the rivers, yet the use of the river has tended to be secondary, if not forgotten. Where rivers are navigable, moorings may be sold with the property; however the opportunity for other uses, such as river buses (see Chapter 6 > Water and Energy Infrastructure), floating property (see Chapter 7 > Aquatecture: Flood-proof Buildings), wetlands and other amenities (see Chapter 5 > Hydroscapes), have been less well considered.

Land alongside rivers may be prone to flooding, therefore waterfront development should take into consideration the risk (see Chapter 1 > Water: Friend or Foe?). Strong governance and clear guidance can prevent inappropriate development, but it still occurs in many countries. When the river floods, objects within the floodplain, such as low bridges or dense development, may inhibit the flood water from conveying (flowing) downstream. Debris carried with the flood can cause structural damage or become trapped, accelerating flow rates around the obstruction. Maintaining or creating floodplain conveyance paths adjacent to a river may be important to reducing flood risk. Chapter 2 > LifE: Integrating Design with Water > Case Study > Site 2 illustrates development arranged into small home zones (arranged around courtyards) between which the gardens and allotments double as floodplain conveyance paths.

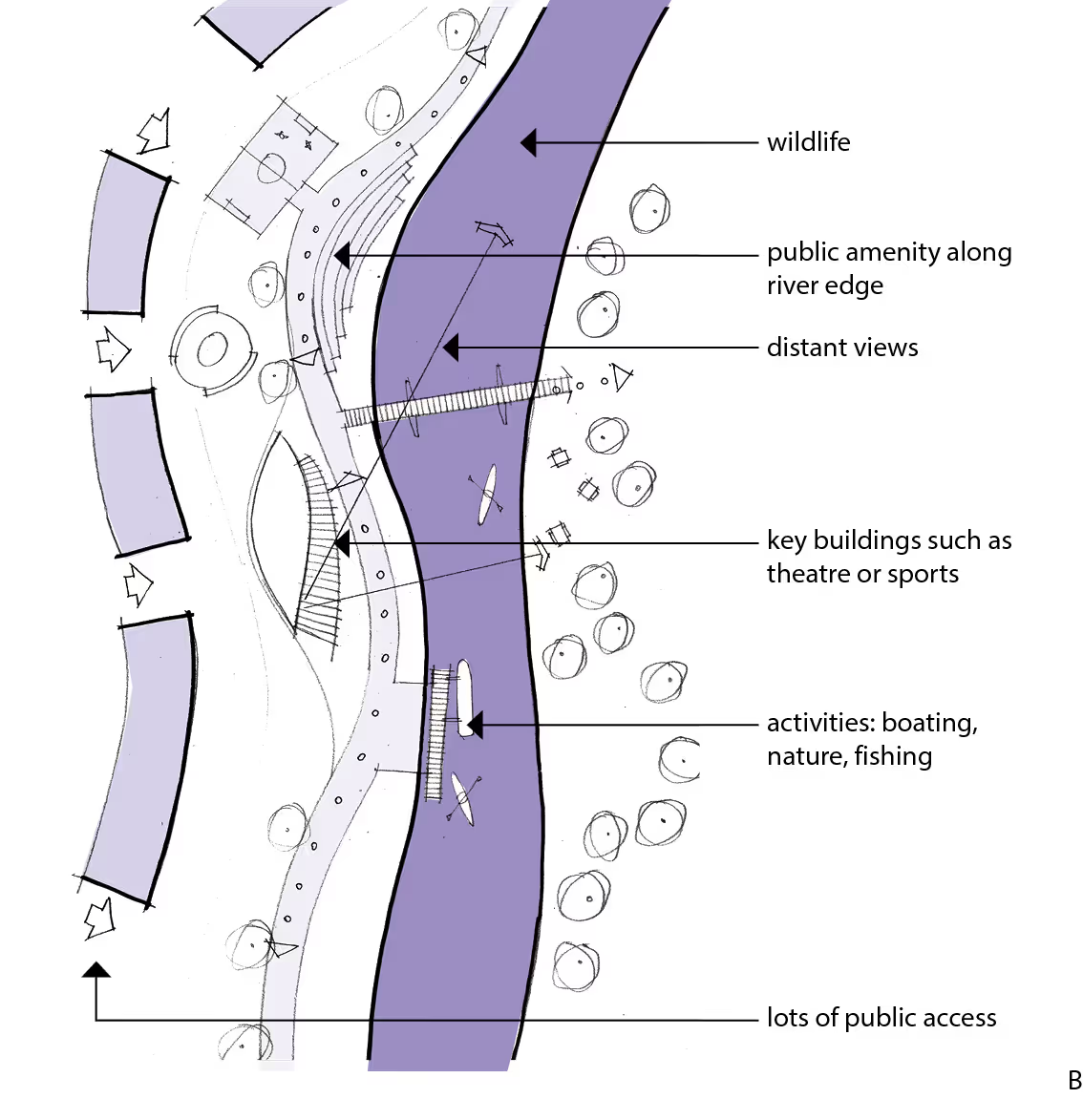

Figure 4.9 illustrates key components of a successful riverside waterfront. River frontages can vary radically according to the nature of the river, whether it be a low-altitude navigable watercourse like the River Rhine (Europe) or a high-altitude rocky river like the Colorado River (USA) or the Yellow River (Africa), or a wide open river like the lower River Yangtze. On navigable rivers, boating, fishing and wildlife bring activity to the water, whereas fast-flowing rocky rivers provide natural interest through white water and wildlife.

Access and continuous walkways can bring activity to the riverside. Where pathways alongside the river may not be possible, pathways over or floating on could be considered, like the floating walkway in Brisbane, Australia.

The sensory connection to the water can be lost when rivers are canalised. Terracing and low-level river walks may improve access to the water. The riverside is well suited for parks and outdoor public spaces as well as habitat corridors, including migratory paths for birds.

When the land is low-lying and subject to flooding, buildings may need to be set back from the river edge to maintain flood corridors/conveyance paths, and to ‘let rivers flow’. Orientating buildings or development parallel to the river as shown in Figure 4.9 may also help. Riverside paths and parks, allotments and secondary roads can be used as conveyance paths. Setting back buildings can create vistas up and down the river.

Building and land uses should be determined according to flood risk. Low-vulnerability uses such as leisure, recreation, parks and civic buildings may be more appropriate closer to rivers than residential or office buildings, both in terms of flood risk and place-making. Where the risk of flooding is greater, elevated and amphibious buildings may need to be considered (see Chapter 7 > Aquatecture: Flood-proof Buildings).

As many rivers form primary arteries through towns and cities the waterfront could be considered in terms of scale, hierarchy, vistas, public realm and the elevation akin to that of a main boulevard and its constituent parts.

Lakes have often been attractive sites for settlement, providing water, a means of travel and food through fishing and other wildlife attracted to the water. A lake is formed at a depression in the rainfall catchment, where the land around prevents the water from flowing out quicker than it is filled. Many lakes are fed and drained by rivers, including Lake Constance on the Rhine, site of the biannual floating stage (see Chapter 6 > Water and Energy Infrastructure), and Tonlé Sap on the River Sap and River Mekong (see Chapter 1 > Water: Friend or Foe?), amongst many others. Another variance is a reservoir, which is typically formed by damming one side of a river valley to create an artificial lake.

A lake or reservoir is part of the water cycle and susceptible to variations in water level, from summer lows to winter highs, and from extreme storm levels and floods. Larger lakes may also be susceptible to wind and wave action. Collapse or failure of a dam structure could potentially release the impounded water with devastating effects. Although the probability of a well-maintained dam collapsing might be low, the consequences can be substantial and therefore the residual risk is a serious consideration.

Large lakes may dampen the velocity and rapidity of flood flows, allowing the opportunity for responsible floating development. Any floating development should consider issues of scale, massing, context and views in the same way that a land-based development would need to, but they should also consider light and water movement below any floating structure to maintain oxygenation (and avoid sterilising the water), and consider access and egress at various water levels (see Chapter 7 > Aquatecture: Flood-proof Buildings). As part of a 500-unit masterplan in Essex, UK, a small development of floating homes is to be built on a lake. The homes are located on the north side to benefit from the southerly aspect and preserve the natural setting to the south. A timber pontoon provides access along the edge of the lake, while still allowing light into the reed beds below.

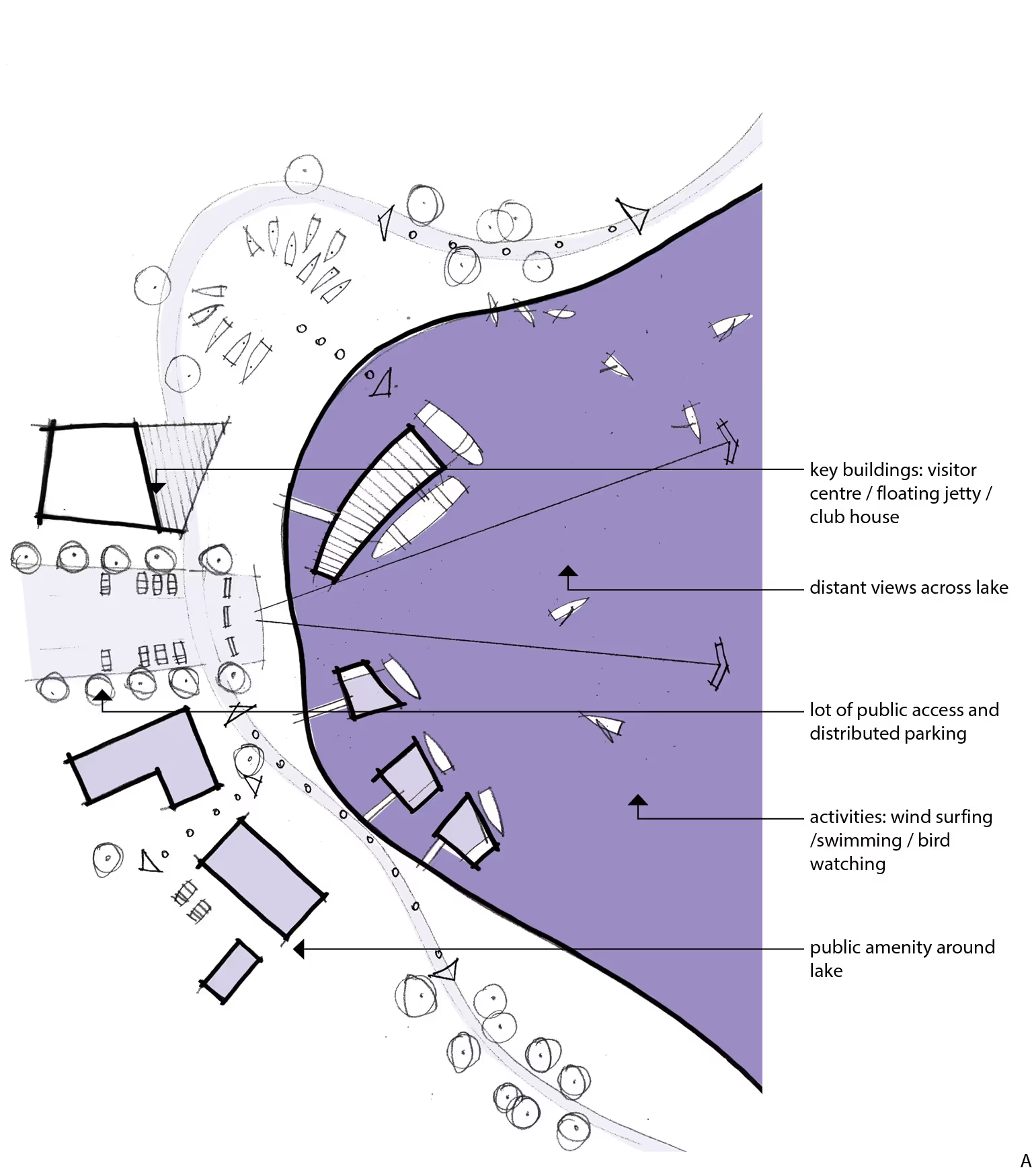

Figure A illustrates some of the key components of a successful lake waterfront. Lakes and reservoirs can provide large open areas in cities and countryside locations. In either context they are an opportunity for access to public space. Pathways around the water can provide valuable recreational space, jogging routes and opportunity to observe the activity on the water. Activities on water may include fishing, boating, canoeing and swimming. Regional lakes may support some industry or shipping.

Residential and leisure uses, as well as holiday accommodation such as hotels and lakeside chalets, are ideally suited to this location. Around larger lakes a mixture of uses may be supported subject to flood risk.

Buildings may be clustered in groups with space in between to preserve the openness of views over the water. Vehicular access can then be restricted to the clusters of development. Clusters of floating development could be considered, such as Brockhole, the Lake District Visitor Centre at Lake Windermere, UK, or offshore chalets in the Seychelles, but it is important to preserve the openness of the water. Key buildings on neighbourhood- or city-scale lakes may be visitor centres and cafés, on larger lakes these may be hotels or civic buildings, supported by local homes and complementary businesses. Lakes and reservoirs can form vital open space in towns and cities and wetland habitats.

It is important to respect and preserve the openness and to plan and control growth and uses similar to the protection of parkland.

The use of small canals for transporting goods has largely been replaced by road and rail networks and it is generally only the large regional shipping canals linking major waterways that are still used in this way. The role of narrow canals has changed to that of recreation and leisure and supporting small communities of houseboats.

The development of the canal system involved many ingenious inventions (see Chapter 1 > Water: Friend or Foe? > Innovation for transport). The slow progression of the water in a downwards direction has been used to traverse over hills, lock by lock, through the midst of Wales, the Highlands in Scotland, and between New York and the Great Lakes. There is something poetic about this manipulation of the natural water cycle and the gentle pace at which one traverses the network of waterways.

In the UK, a dedicated organisation called the Canal & River Trust was established to manage and maintain the network of canals and waterways. Narrow canals have become attractions for leisurely holidaymakers, ramblers and wildlife. Canals in urban areas were often lined with warehouses to take goods directly off barges, many of which have now been converted to apartments by developers appreciating the value of water as a backdrop.

The canal structure may present a risk of flooding to surrounding land, particularly if it is elevated above adjacent settlements of flooding. The land may be subject to surface water and fluvial flood risk from river connections (see Chapter 1 > Water: Friend or Foe?).

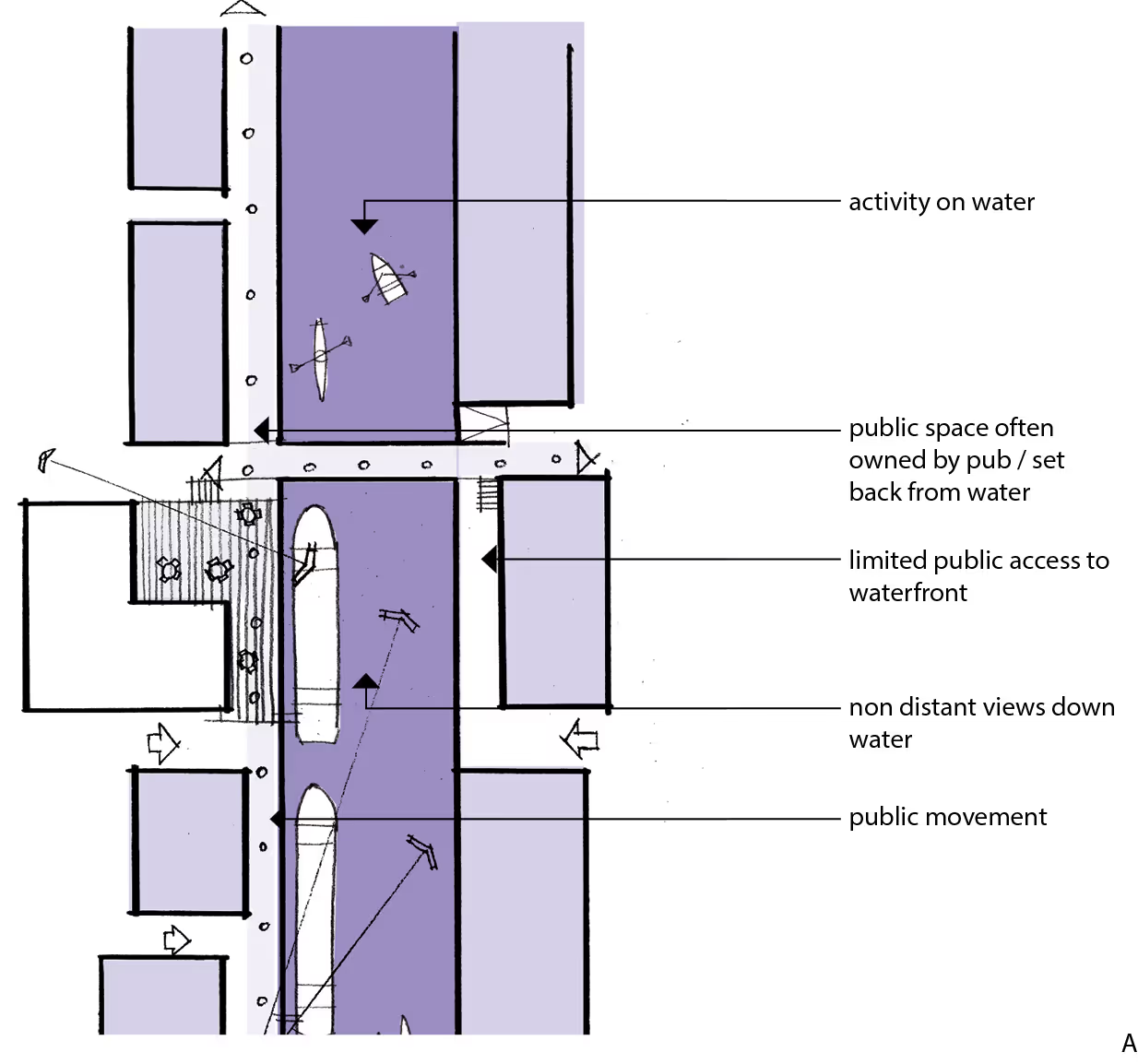

Figure 4.11 illustrates some of the key components of a successful narrow canal waterfront (for larger canals within this chapter). The calm water in a canal can create a peaceful character and narrow canals can feel more intimate than many rivers. Public space often takes the form of pockets of land, with access or views over the water. The buildings lining the waterspace may limit views up and down the canal, reinforcing the intimate relationship with the water. Public footpaths can be quite modest but should be wide enough for pedestrians and cyclists to pass. Where continuous public walkways are not possible they can meander inland before returning to the canal side.

Small boats, gentle water sports, houseboats and wildlife can provide activity on water. Where canals meet other waterways this can be an opportunity for arrival points and mooring points. These are often the locations for water fetes and carnivals.

Building up to the water’s edge may provide variety, particularly where they have public/private space over the water and colonnades could maintain footpaths. Building heights that are scaled to the width of the water reduce overshadowing. A bar, restaurant or pub may form a local landmark or destination.

Canals can provide access to water where there are no rivers. They can be an opportunity for hydroscapes (see Chapter 5 > Hydroscapes) and sustainable drainage. Access, character, heritage and variety of uses both on and off the water can help to maintain their vitality and role in the 21st century.

Harbours and inlets provide the interface between the land and the sea and are the reason for the location of many towns. The shipping and fishing industries have outgrown the scale of many historic harbours, resulting in their conversion to marinas for leisure craft. The international demand for moorings continues to rise. This is not exclusive to warmer areas like the Bahamas or the Mediterranean but includes more temperate climates.

Usually hard-edged and ‘urban’ in character, harbours are not obvious havens for wildlife, however examples such as the (Australia) demonstrate that moorings and wildlife can coexist.

Harbours, either man-made or natural, are open to the sea but protected by breakwaters. This means that they enjoy the ebb and flow of the tides but may be subject to storm surges, hurricanes/cyclones, tsunamis and sea level rise. The harbour arm may provide some protection but unless a floodgate is introduced to shut the harbour off from the sea it will not prevent flood risk from extreme tides.

Leisure facilities and promenades provide scope for public access to the water. However, security measures may restrict access, therefore a combination of public and private paths or pontoons may be required.

Harbours, by nature, tend to be open-sided and therefore can support taller buildings without necessarily overwhelming or overshadowing the waterspace. Elevated views over the water can attract visitors and provide varied articulation and scale to create a well-composed waterfront.

With access to the sea, harbours are ideal places for marinas and non-permanent floating vessels. Leisure boats and marina facilities create regular activity on water. Floating pontoons and moorings can allow the waterspace to be rearranged for special events and shows.

Floating or fixed pontoons can be designed to allow shared vehicular access to the boats and water’s edge. Security needs to be considered and therefore public access may be limited to certain areas and/or times of day. It is preferable not to permit car parking to dominate and to locate it out of sight, such as below ground in secure, managed facilities or set away from the water’s edge.

In Littlehampton, UK, a new marina is envisaged not just as a place to moor boats but as part of an architectural ecosystem in which an artificial tidal lagoon, created as a flood store, is part marina, part salt marsh and part tidal power generator (see Chapter 2 > LifE: Integrating Design with Water > Case Study > Site 3). The marina would have an urban character on the riverside, defined by the hard river defences, but would have a natural character defined by the reeds on the lagoon. The land is tiered down to both the river and the lagoon so that residents and visitors can get close to the water and feel connected to this dynamic environment.

Harbours and marinas provide a wonderful opportunity to access the sea. They are often the raison d’être of many coastal towns and a large part of their character. Historic features of the harbour may warrant protection but it is the dynamism of their use (like the ebb and flow of the tide) that should be nurtured and enhanced.

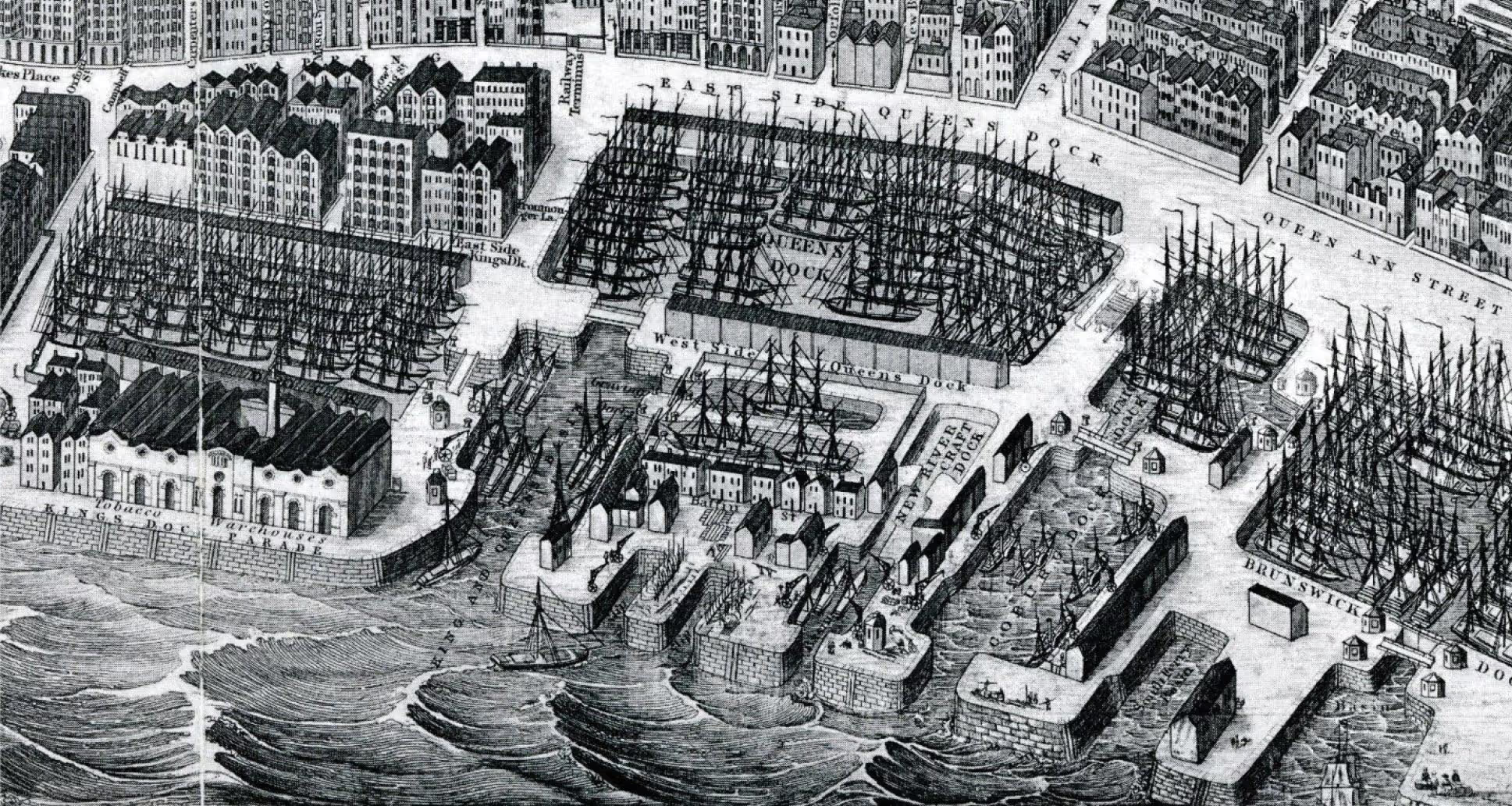

Docks, wharfs and shipyards have been instrumental for trade for thousands of years to facilitate handling vessels, goods and people. Many docks were created on reclaimed land in flood-prone areas on the outskirts of settlements. These vast, often windswept landscapes were transformed by the daily passage of ships, tugs and other maritime vessels, some of which would tower over the static warehouses (see Figure 4.15). Redevelopment has reversed the balance by creating towers on land that overlook and overshadow the neglected waterspaces.

Like harbours, many docks have become redundant waterspaces as shipping has moved to larger modern facilities. Historic waterspaces, once on the edges of cities, have largely been absorbed by urban growth and have since been the focus of regeneration, such as HafenCity in Hamburg (Germany), Malmo (Sweden) and Toronto (Canada) (see Chapter 1 > Water: Friend or Foe?). These areas sometimes benefit from the historic infrastructure that supported the docks.

Dock edges are often several metres above the water level as they were designed to allow easy access on and off large vessels. This can make access to the water difficult for smaller boats. In some cases, it is possible to artificially raise the water level, but this is dependent on the height of the tides and condition of lock gates and dock walls.

Where flood defences provide protection to the docks (such as impounded docks), floating development may be economically viable and sustainable. However, the residual risk of flooding behind the defences must still be managed and the effects of a breach considered (see Chapter 1 > Water: Friend or Foe?). Floating development can enable access to local facilities and transport, with minimal hard-infrastructure requirements of its own.

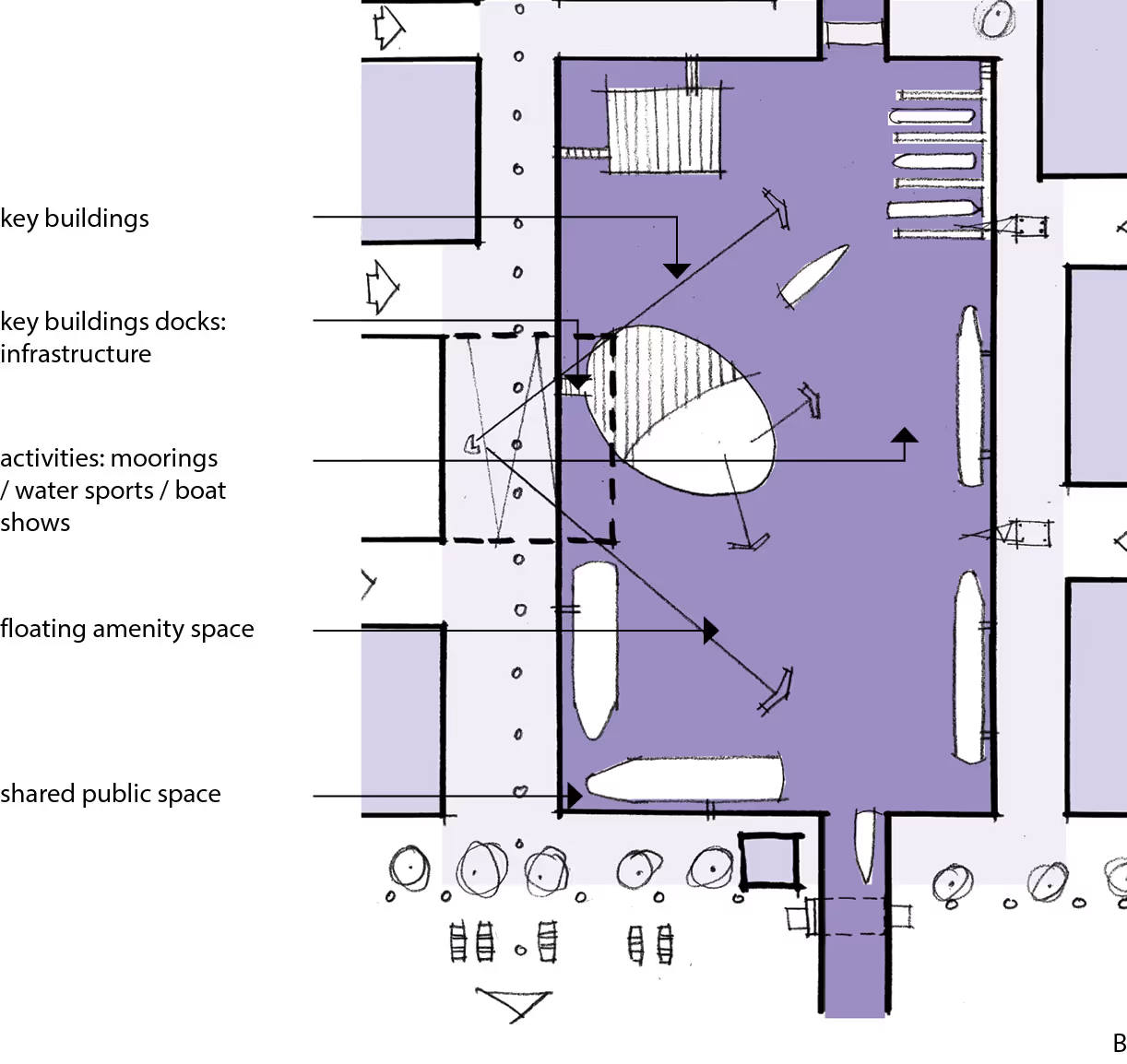

Figure 4.16 illustrates some of the key components to create a successful dock waterfront. Large quaysides and wharfs can create generous public spaces along the water’s edge. New buildings and structures can ideally be designed to reduce winds. Quaysides were historically multifunctional and this should be continued, with shared surfaces for cars, cyclists and pedestrians along with kiosks and small buildings. Gaps between quayside buildings or stepped façades can reduce overshadowing to the public realm and water.

Static (or managed) water may be suitable for floating development. The depth of the water, which can be in the order of 10 m, may support large floating structures and therefore a greater variety of uses, such as hotels, shopping and parks. Where located along the dock edge, floating buildings and structures can be used to aid the vertical transition from the land to the water. However, in larger dock spaces floating development may be best located away from the dockside, to retain views of the water and accommodate ramps for wheelchair, cycle and vehicular access.

The scale of the activity on water should seek to reflect the scale of the dock; small interventions can be lost if set in expansive waterscapes. Water sports, motor boats, large sculptures, floating stages, ice rinks, even car parks and stadiums, may all be considered. The dock edge is often large enough to accommodate spectator crowds. Many of these activities rely on sufficient visitor numbers to be successful; therefore, shopping facilities or a landmark public building can help stimulate year-round interest. For example, in London’s Royal Docks an artificial surf centre has been planned that, combined with an aquarium, will form a visitor attraction alongside 5,000 new homes (see Chapter 6 > Water and Energy Infrastructure).

Large city-scale docks may require comprehensive planning and could support a range of uses including leisure moorings and water sports, floating homes and businesses, and cultural uses, while providing open waterspace for navigation. In post-industrial nations the trend has been to convert warehouses into apartments with retail and restaurants at the ground level. The floating development may house a range of uses, subject to flood risk.

Former docks present an ideal opportunity and suitable setting for communities built on water. But the water deserves to be masterplanned with the same rigour that one would apply on land to ensure that a vibrant and successful mix of uses helps to maintain the water and support the city. A comprehensive plan for the Liverpool South Docks, shown on the following page, sets out a vision and long-term plan for the sustained use of the water to revitalise this UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Coasts and deltas are the most habited waterfronts on Earth. The fertile soils of river deltas support crops and animals while the coast provides access to the riches of the sea. These waterfronts are also the most dynamic, subject to erosion, sedimentation, flooding, storm surges and sea level rise. Many nations invest substantial resources trying to restrain this change with groins, rock armour, coastal defences and beach restoration. Despite this effort the sea will slowly erode and wear down coastlines if it does not rise above them first. Whole towns and villages have been abandoned as a result of the action of the sea eroding the cliffs on which they were built.

People choose to live in coastal locations for qualitative as well as pragmatic reasons and it is likely that this will continue to be the case. The coast offers a rare glimpse of an uninterrupted, limitless horizon. Research has identified that good health is more prevalent the closer one lives to the coast, perhaps a result of better views of the sea, cleaner air or healthier lifestyles. Coasts can contain some of the most beautiful landscapes but many are built on with development that seeks to enjoy the view of the water but often neglects to consider the view back from the water.

The main flood threats to coastal settlements are from tidal storm surges and from erosion, which can be exacerbated during a storm. Many nations rely on flood defences for protection, however these are only as good as their engineering and scale. In 2011, the tsunami that hit Japan overtopped and destroyed some of the flood defences; it proceeded to destroy almost all buildings in its path (even those designed to be flood-resilient) and killed over 15,000 people. In some locations flood defences may be the best solution, particularly where they provide protection for large populations, but the residual risk should not be overlooked. Flood defences may reduce physical and visual access to the sea or water, giving inhabitants a false sense of security that could potentially be life-threatening. Vantage points and robust early warning systems could help to increase awareness and reduce risk.

Flood defences can be integrated with landscape and public realm to provide amenity and benefits to neighbourhoods and the city (see Chapter 6 > Water and Energy Infrastructure). Wetlands can also help to reduce storm energy (see Chapter 5 > Hydroscapes).

In low-lying coastal situations, safe havens (both for humans and livestock) need to be designed to an extremely high standard of protection and potentially raised on artificial hills, known as ‘terps’.

To respond to the dual threat of erosion and flooding, a dynamic approach may be required.If land were to be thought of as transient, the opportunity for temporary occupation and non-permanent residence or functions that change over time may be considered. Chapter 10 > Case Study: City > Shanghai, Future City explores how one land use can change to become more water-compatible as sea levels rise.

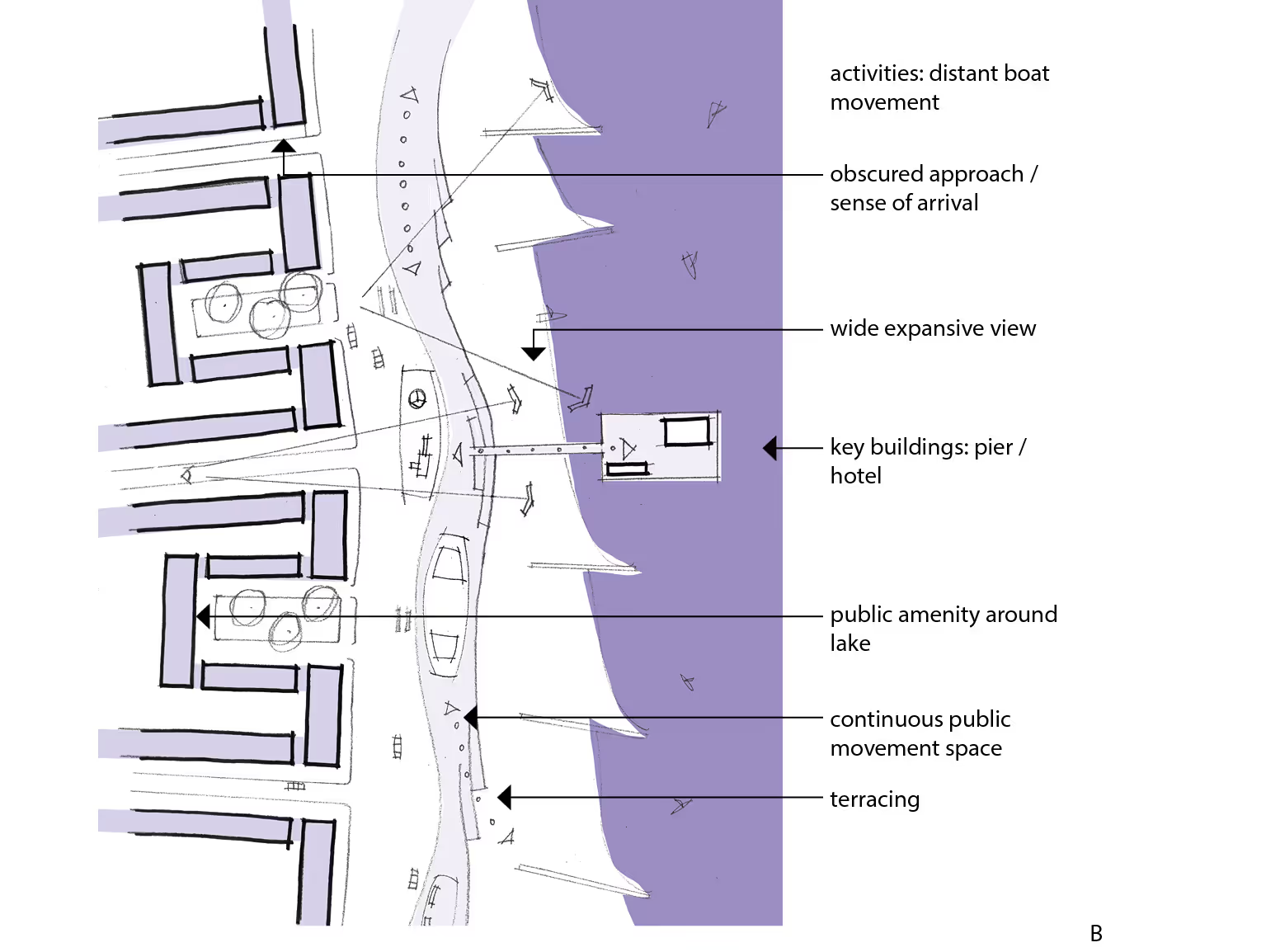

Figure B illustrates some of the key components to create a successful coastal waterfront.

Seafronts define the edge between land and sea; they are the edges of the known territory and the start of the unknown. The most successful seafronts are ones where there is generous public access, the opportunity to promenade along the seafront and to enjoy the distant views. The seafront/beach should ideally be preserved for public use or nature. Piers may provide an extension of the public realm into the water and are often a key landmark or attraction, as are miradors, which are often located at high points on coastlines to provide uninterrupted panoramic views (see Chapter 6 > Water and Energy Infrastructure).

Access to the water for bathing, water sports and just sitting can give animation to the seafront.

A selection of accessible buildings, such as restaurants, nightclubs, sports centres, shops, theatres and museums can all provide attractions. The sea forms an edge to the town, resulting in a linear frontage. Therefore uses may be organised into clusters along the front, such as a retail zone, a restaurant zone, extending into residential and commercial zones, or it can be more mixed-use, with vertically stacked uses. Vertically stacking uses can be organised according to flood risk, with less vulnerable uses on the ground floors.

A continuous line of buildings on the front can create a sheer wall to the sea and town and lack public generosity. Balconies, set-backs and profiled rooflines can create better articulation. Gaps between buildings on the seafront allow views of the sea and the sound of the waves from buildings behind, creating a more accessible and connected waterfront.

Roads are often located on seafronts and these can provide activity, particularly during inclement weather. However, movement by car, especially during holiday seasons, needs to be balanced with space for pedestrians. Shared surfaces offer flexibility, improved safety and provide accessibility for all.

Seafronts are the threshold between land and water and therefore they deserve to be treated with consideration from both the town and from the perspective of the sea.

Delta landscapes can occupy huge regions. Figure A illustrates some of the key considerations. Bangladesh (figure B shows a satellite view of the Sundarbans delta) and the Netherlands are almost entirely founded on river deltas. City-scale settlements tend to be located inland along the edge of major rivers rather than at the extremities of the land, where it meets the sea.

Within the delta landscape the dynamic interchange between the tide and the land can transform the landscape on a daily basis, making settlement precarious. Storm surges or peak river flows can overwhelm the land. Safe routes to remote property can be difficult to achieve so individual property protection may be required, including elevated and amphibious construction (see Chapter 7 > Aquatecture: Flood-proof Buildings).

Activity on water or land should be sensitive to the wildlife of these important habitats. Public access should be in safe areas and restricted from sensitive habitats. Boardwalks, meandering paths and selective viewing points may form part of the public realm.

Development use should take into consideration flood risk but is likely to be best located on higher ground and in small clusters.

Discrete visitor centres, birdwatching hides, wildlife sanctuaries and research centres may form key buildings and destinations.

Deltas and wetlands are some of the most valuable and biodiverse habitats in the world. Development in this environment requires an understanding of the synergy between land and water and the potential for change.

Many of the projects illustrated in this chapter have sought to retain the waterside industrial heritage, such as docks, cranes and piers, within redevelopment plans. However, they have predominantly been land-based development, alongside the water, with little engagement or use of the waterspace. Those that do engage with and use the water give it value and maintain a reason for its existence.

The key to successful waterfront planning is activating the water. It is a balance between managing the flood risk and enjoying/engaging with the water. This can be defined in two ways:

Physical engagement, such as activity and use of the water, as well as access to the water and the spaces along the waterside.

Sensory engagement, particularly views of the water, but also hearing the sound of the water or the smell of the sea.

The combination of the physical and the sensory helps to create vibrant and self-sustaining destinations. Creating active uses of the water can help to bring revenue to contribute to the ongoing maintenance costs as well as maintain the need for the water in the hearts and minds of residents and visitors. The most successful waterfronts, those that leave a lasting memory and compel one to return, contain a healthy mix of both physical and sensory engagement.

Physical engagement/activity can be as simple as providing an area for people to swim (such as a beach), fish or sail, or extend to more intensive uses like a water taxi, ferry terminus, theatre or floating sports centre.

Visual engagement/surveillance may also be very varied – from having footpaths along waterways such as the timber walkway over the River Cam in Cambridge, to great waterside piazzas like St Marks in Venice, to wharfs or piers projecting over the water, such as the Chelsea Piers in New York.

The common characteristic of all of these is public space. Although it may be desirable for developers or property owners to create private waterfronts, it is essential to create public space, as it is footfall that contributes to an active waterfront.